This is an article from the European Space Agency

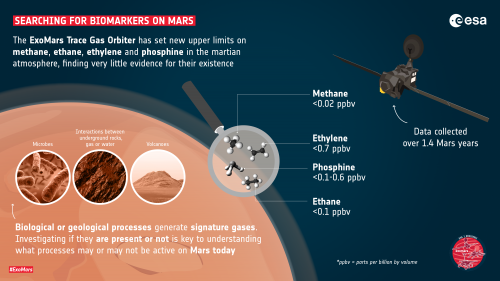

New findings from the ESA-Roscosmos Trace Gas Orbiter set new upper limits on how much methane, ethane, ethylene and phosphine is in the martian atmosphere – four so-called ‘biomarker’ gases that are potential signs of life.

Searching for biomarkers on Mars is a primary goal of the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. A key biomarker of interest is methane, as much of the methane found on Earth is produced by living things or geological activity – and so the same may be true for Mars.

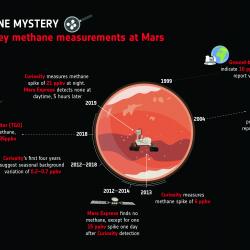

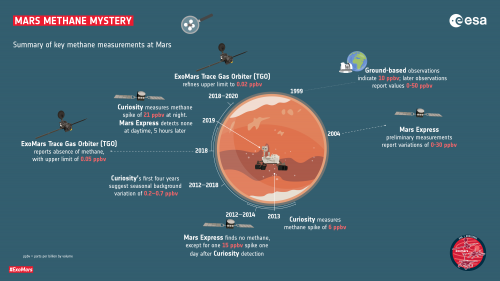

The ‘methane mystery’ on Mars has been ongoing for many years, with contradictory findings from missions including ESA’s Mars Express and NASA’s Curiosity rover capturing sporadic spikes and bursts of the gas in Mars’ atmosphere, fluctuations both in orbit and at the planet's surface, signs of the gas varying with the seasons, or not observing any methane at all.

Previous estimates from Mars Express and ground-based missions range from 0.2 up to 30 ppbv (parts per billion by volume), indicating up to 30 molecules of methane per billion molecules. For reference, methane is present in Earth’s atmosphere at nearly 2000 ppbv.

However, the first results from the Trace Gas Orbiter, reported in April 2019, spotted no methane, instead calculating that, if present, the gas must have a maximum concentration of just 0.05 ppbv.

Franck Montmessin of LATMOS, France, Co-Principal Investigator of the Trace Gas Orbiter’s Atmospheric Chemistry Suite (ACS) and lead author of one of a trio of new papers on martian biomarkers:

We have now used the Trace Gas Orbiter to refine the upper limit for methane at Mars even further, this time gathering data for over 1.4 martian years – 2.7 Earth years. We found no sign of the gas at all, suggesting that the amount of methane at Mars is likely even lower than previous estimates suggest.

As the orbiter’s instruments are highly sensitive, if methane is present it must be at an abundance of less than 0.05 ppbv – and more likely less than 0.02 ppbv, say Franck and colleagues. The scientists also hunted for signs of methane around Curiosity’s home, Gale crater, and found nothing, despite the rover reporting the presence of methane there.

“Curiosity measures right at Mars’ surface while the orbiter takes measurements a few kilometres above – so the difference between these two findings could be explained by any methane being trapped to the lower atmosphere or the immediate vicinity of the rover,” adds Franck.

The apparent lack of martian methane reported by Franck and colleagues is supported by a paper using data from the orbiter’s NOMAD instrument (BIRA-IASB), again spanning a full martian year and searching for methane and two other biomarkers.

The paper’s lead author Elise Wright Knutsen, previously at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, USA, and now at LATMOS, France:

We also found no sign of methane on Mars, and set an upper limit of 0.06 ppbv, which agrees with TGO’s initial findings using ACS. As well as searching for global methane, we also looked for localised plumes at over 2000 locations on the planet and didn’t detect anything – so if methane is released in this way, it must be sporadic.

Alongside methane, Elise and colleagues looked for two other potential biomarker gases: ethane and ethylene. These molecules are expected to occur after methane is broken down by sunlight, and so are exciting both in their own right and in the context of our hunt for methane. Ethane and ethylene molecules also have short lifetimes, meaning that if they are found in a planetary atmosphere they must have been recently released or created via an ongoing process. This makes them excellent tracers of possible biological or geological activity.

“These are ExoMars’ first results hunting for these two gases,” says Elise. “We didn’t detect either, and so set upper limits for ethane and ethylene at 0.1 and 0.7 ppbv, respectively – low, but higher than our limits for methane.”

The orbiter has also been hunting for phosphine – a gas that caused a splash and huge controversy last year when it was allegedly detected at Venus. Most phosphine on Earth is biologically produced, making it an exciting biomarker in the atmospheres of terrestrial planets. “We didn’t find any signs of phosphine at Mars,” says Kevin Olsen of the University of Oxford, UK, and lead author of the phosphine study. “Our upper limits are similar for those of ethane and ethylene – between 0.1 and 0.6 ppbv.”

The search for life on Mars, or lingering signatures of it, is a central goal of the ExoMars programme, and the hunt for biomarkers in particular is a primary goal of the Trace Gas Orbiter. The forthcoming ExoMars rover Rosalind Franklin, due for launch in 2022, will complement TGO’s hunt for biomarkers by digging down into the martian surface; underground samples may be more likely to retain biomarkers, as material is shielded from the harsh radiation environment of space.

Håkan Svedhem, ESA Project Scientist for the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter :

Whether biomarkers are detected or not, these findings are important for our understanding of which processes occur, and which do not, in the martian atmosphere – essential information when considering where to focus our continued investigation of Mars. Many key questions remain – for instance, why does Curiosity see methane at Gale Crater, while we find none in orbit? Could this methane have come from elsewhere, or only be found in particular locations across the planet – or could an unexpected process be destroying any methane present before we can detect it?

It will be exciting to continue working collaboratively with missions like the Curiosity and Rosalind Franklin rovers, both of which have totally different vantage points to an orbiter, to really pin down what is happening in this mysterious planetary environment.

This article is based on three papers:

"A stringent upper limit of 20 pptv for methane on Mars and constraints on its dispersion outside Gale crater" by F. Montmessin et al. is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140389

"Comprehensive investigation of Mars methane and organics with ExoMars/NOMAD" by E. Knutsen et al. is published in Icarus. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.114266

"Upper limits for phosphine (PH3) in the atmosphere of Mars" by K. Olsen et al. is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140868

Credit: ESA/Roscosmos/CaSSIS, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

The gases are often associated with biological or geological processes, so understanding if they are present or not on another planet is key to understanding what processes may or may not be active on Mars today.

Credit: ESA

Credit: ESA